🥞 Branded Lies: When the Logo Whitewashes History (Part 3)

Part Three of 'Oops, We Made It Worse' (Part 3 of 7 Part Series)

Top of the Series: 🧯 Oops, We Made It Worse (Part 1)

Previous: 🧃 What Were They Drinking?! (Part 2)

Oops, We Made It Worse – Part 3: 🥞 Branded Lies: When the Logo Whitewashes History

Welcome back to our ongoing series where we highlight branding disasters so bold, so misguided, they practically come with their own warning labels. Today’s subject? A warm smile, a comforting plate of pancakes, and a history so uncomfortable it could curdle syrup. Let’s talk about Aunt Jemima—and the enduring legacy of marketing built on fiction, fantasy, and flat-out falsehoods.

If you're interested in how distorted narratives—whether in branding or the boardroom—can shape culture and collaboration, stay tuned for my upcoming book Collaborate Better. It’s packed with insights on dismantling outdated myths, building authentic connections, and leading teams with clarity, empathy, and a shared purpose.

🤔 Fact or Fiction? The Mascot Myth Quiz

Recently, social media has been abuzz with posts claiming that beloved brand mascots like Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben, and Cream of Wheat’s Rastus were all real people—historical figures allegedly erased by modern rebranding. These claims are often loud, emotionally charged, and deeply inaccurate.

To set the record straight—and test your brand literacy—let’s play a quick round of Fact or Fiction. Ready?

Which of the following brand mascots was based on an actual historical person?

A) Aunt Jemima

B) Uncle Ben

C) Rastus (Cream of Wheat)

D) None of the above

Take a second to guess.

All three were marketing inventions, rooted in stereotypes, created and controlled by white-owned companies. While some real Black individuals were hired to portray these mascots at events or in ads, the characters themselves were fictional. Their origins weren’t biographies—they were brand strategies, born in boardrooms and shaped by the cultural blind spots of the times.

🌾 The Smiling Lie on Your Breakfast Table

For generations, Aunt Jemima was the face of breakfast in America. Cheerful. Familiar. Fictional. What many didn’t realize—or didn’t want to think about—was that this smiling woman was born not from a family recipe, but from a 19th-century minstrel show. Literally.

The name "Aunt Jemima" was lifted from a minstrel tune written by a white performer in blackface. Later, two white businessmen decided this character would be the perfect mascot for their new self-rising pancake mix. Over the next century, Quaker Oats leaned into the stereotype, even paying Black women to portray her at promotional events. That’s not heritage—it’s PR gloss on a deeply racist trope.

Discover more in my video exploration of the Aunt Jemima story

🧵 The Mascot Playbook: Cozy Characters, Ugly Origins

Brand mascots often walk a delicate line. When done right, they humanize a product. When done wrong, they dehumanize a people. Aunt Jemima wasn’t alone.

Uncle Ben was once a symbol of domestic servitude before being upgraded to “CEO” in a corporate plot twist that fooled exactly no one.

🍚 Who Invented "Uncle Ben’s"?

Uncle Ben’s was first launched in the 1940s by Converted Rice, Inc., a company that had developed a method of parboiling rice to retain nutrients. The technology was used by the U.S. military during World War II for its longer shelf life, and the rice’s success led to a consumer brand created in partnership with Mars, Inc., the company best known for candy, pet food—and, for decades, rice.

Uncle Ben’s rice hit store shelves in 1943, marketed as premium, high-quality rice that cooks consistently. But the face on the box—and the name—weren’t invented out of thin air. They were chosen for very specific, and very problematic, reasons.

👴 Who Was “Uncle Ben”?

According to the company, “Uncle Ben” was inspired by a real man—a Black Texan farmer who was renowned for growing exceptionally high-quality rice. However, that man was never involved in the company, and his full identity was never officially confirmed or publicly credited.

The image used on the packaging? That was reportedly based on a photo of Frank Brown, a Chicago maitre d’ at an upscale restaurant. He was asked to pose in a white dinner jacket and bow tie to create the now-iconic image: a smiling, servile older Black man.

This is where things get ugly.

🎩 “Uncle” as a Racialized Title

The term “Uncle” was historically used in the Jim Crow South to refer to Black men in positions of domestic servitude—especially when white people wanted to avoid giving them the respect of titles like “Mr.”. It echoes the same system that gave us “Aunt Jemima”—a way of sanitizing Black labor through comforting imagery while maintaining the power dynamics of the plantation and the servant class.

“Uncle Ben” was never positioned as an innovator, business owner, or leader. He was the smiling cook, the ever-reliable kitchen helper, the invisible hand in the pot. He represented domesticity and service. He was polite, passive, and perfectly non-threatening.

And for decades, it worked. Uncle Ben became one of the most recognizable food brands in America.

🧑🏽💼 The “CEO” Plot Twist: Corporate Damage Control

Fast forward to the 2000s, when the brand’s problematic roots started to clash with evolving public awareness. Facing growing criticism over the racially coded nature of the mascot, Mars tried a bold (and wildly awkward) pivot.

In 2007, the company declared Uncle Ben had been “promoted” to Chairman of the Board.

They launched a rebranding campaign that featured Uncle Ben—still in his bowtie and dinner jacket—now seated behind a big corporate desk, looking over documents. They wanted to suggest that Ben was no longer a servant… now he was a boss.

The campaign landed with a resounding thud.

Critics saw through it immediately. It was obvious Uncle Ben hadn’t earned his promotion through a compelling backstory or legacy of innovation—he’d just been dressed up and dropped into a boardroom like a prop. The white jacket stayed, the title changed, but the symbolism didn’t. The entire rebrand felt like a shallow PR stunt, trying to modernize optics without actually addressing the deeper racial undertones of the brand’s origin.

🔥 What Finally Prompted Change?

The turning point came in 2020, following the murder of George Floyd and the worldwide protests that followed. The U.S. experienced a massive reckoning around systemic racism, and companies came under intense scrutiny for how they perpetuated racial stereotypes in branding.

Under public pressure—and amid a broader cultural wave of accountability—Mars finally took real action.

In 2021, the company:

Officially retired the “Uncle Ben” name

Removed the image of the elderly Black man from all packaging

Rebranded the product as Ben’s Original

They also pledged to support racial equity through community outreach programs and donations—but critics still noted that it took nearly 80 years and a global protest movement for a company to finally re-evaluate a logo that had never aged well.

🎭 The Symbolism

Uncle Ben is the original “promotion without power” story.

He was a symbol of domestic servitude, upgraded to “CEO” in a corporate plot twist that fooled exactly no one.This wasn’t just about outdated imagery—it was about the performative nature of corporate DEI gestures, the power of branding to encode systemic values, and how companies often resist meaningful change until public pressure makes it inescapable.

📝 TL;DR

Created: 1940s, by Mars Inc. and Converted Rice

Based on: A Black rice farmer’s reputation and a maitre d’s image

Name/title: “Uncle” used instead of “Mr.”—a racial norm of the Jim Crow era

Attempted rebrand: Promoted to “Chairman” in 2007—universally panned

Actual change: Dropped name & image in 2021 → Ben’s Original

Why it matters: A case study in how brands can embed, ignore, and eventually confront the racism baked into their legacy

Rastus, the Cream of Wheat chef, was another cheery servant whose existence centered on feeding white families.

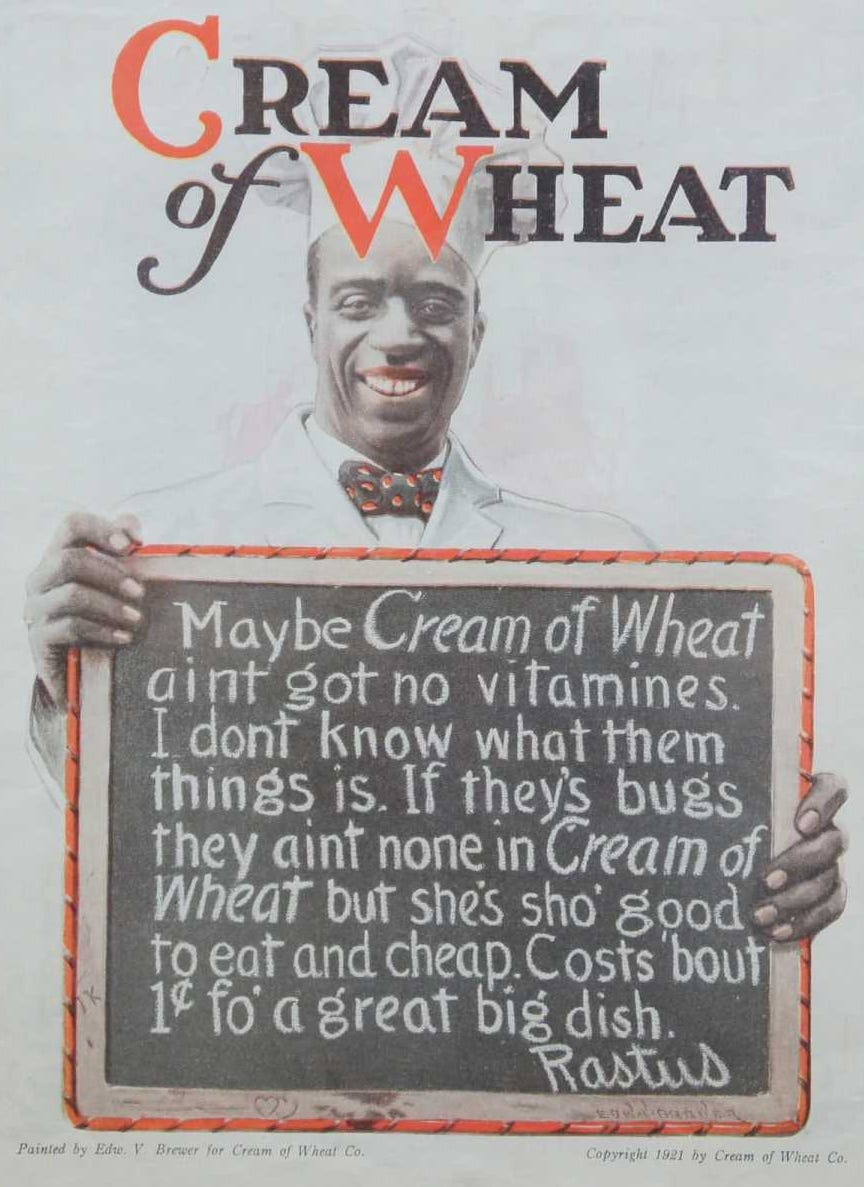

“Ever notice how mascots like Rastus weren’t allowed proper grammar? Turns out, ad execs loved a bowl of stereotypes with their breakfast.” 🍽️ Rastus, the Cream of Wheat Chef

“Smiling from the box, but never from a place of dignity.”

For over a century, the face of Cream of Wheat featured a smiling Black chef—cheerful, tidy, and ever-ready to serve up a hot bowl of porridge. His name? Rastus.

To modern audiences, it sounds like a relic from the past. But for generations of Americans, Rastus was an emblem of breakfast comfort—and a deeply entrenched symbol of racial servitude.

🧑🏿🍳 Who Was “Rastus”?

Let’s be clear: Rastus was not a real person.

He was a fictional character, crafted by marketers and ad men in the late 1800s to project a sanitized, cheerful image of the post-slavery Black domestic worker.The name “Rastus” itself was commonly used during the Jim Crow era as a generic, stereotypical name for Black men, especially those depicted as subservient, happy-go-lucky, and simple-minded. It was the minstrel-show equivalent of calling every Black servant “Boy.”

When Cream of Wheat was launched in the 1890s, the brand chose Rastus as its mascot to signal warmth, trustworthiness, and humble domesticity—coded in the form of a Black man whose sole identity was to cook for white families.

He was always shown in a chef’s uniform, beaming with delight, ladle in hand. Never aging. Never speaking. Never doing anything but serving.

🗞️ Advertising and the “Happy Servant” Myth

Cream of Wheat ads didn’t just use Rastus—they leaned into the stereotype hard.

Early 20th-century ads often featured Rastus offering patronizing commentary in heavy dialect—reinforcing the trope of the illiterate, jovial servant whose life revolved around feeding his white “family.”

He wasn’t a person. He was a marketing fantasy: the perfect servant, eternally loyal, never asking for a raise, always smiling while stirring the pot.

This wasn’t an accident. It was a deliberate play on nostalgia for a “simpler” time—one that was deeply racist, evoking the plantation-era myth of the “happy slave” who was content in servitude.

It made white customers feel at home. It made Black identity a cartoon.

🎭 The Legacy of Rastus

While some companies phased out their racist mascots slowly over the years, Cream of Wheat kept Rastus on the box for well over a century.

Even as social norms changed and other brands began to reckon with their imagery, Rastus remained—his appearance slightly modernized, but his symbolism intact. The chef’s name was eventually dropped, and the image updated with different models, but the core idea persisted: the smiling Black man who served without question.

This slow evolution masked a refusal to fully reckon with the brand’s origins. Changing the art without addressing the context is like repainting a monument without reading the plaque.

🧨 The Reckoning (Finally)

Similarly to Uncle Ben, in the summer of 2020, after the murder of George Floyd and the nationwide protests for racial justice, corporations across the board faced a cultural reckoning.

Activists and consumers began asking hard questions:

Why is this imagery still around?

What message does it send?

Who gets to be the face of your brand—and who gets flattened into a stereotype?Bowing to pressure, B&G Foods, the parent company of Cream of Wheat, announced it would remove the image of the Black chef from all packaging.

They admitted what critics had said for decades: the depiction was rooted in a legacy of racial stereotyping and no longer reflected the company’s values.

The image was retired in late 2020, marking the end of Rastus’ official presence on the box. But the brand made no significant narrative shift. There was no replacement face. No real reckoning in the marketing. Just silence and a redesigned box.

🔍 What’s the Problem With the Character?

He’s not a character. He’s a caricature.

He was created to comfort white audiences through the image of a subservient Black man

His name and mannerisms were drawn from minstrel shows and racist stereotypes

He offered no agency, no personality, no purpose beyond service

He reinforced the idea that Black existence is best when it’s cheerful, compliant, and silent

📝 TL;DR

Created: 1890s

Name origin: “Rastus” was a common racial caricature name

Role: Cheerful, subservient Black cook made to comfort white consumers

Ad portrayal: Illiterate dialect, servile posture, eternal smile

Retired: Officially removed from packaging in 2020

Why it matters: Rastus isn’t just outdated—he’s the embodiment of how brands have profited from racial stereotypes for over a century

🧠 Final Thought

Rastus didn’t feed America.

He fed a fantasy: that racial inequality could be packaged with a smile and stirred into breakfast without consequence.Cream of Wheat didn’t just sell porridge—it sold a comforting lie about who belongs in the kitchen, and who gets to be seen in power.

It’s easy to retire a face.

It’s harder to unlearn the system that thought that face was ever acceptable.The Frito Bandito was a mustachioed caricature who, somehow, made it out of committee and onto TV screens.

🌮 The Frito Bandito

“He came for your chips—and your dignity.”

In the pantheon of branding misfires, few mascots are as jaw-droppingly offensive as the Frito Bandito—a cartoonish, sombrero-wearing, pistol-toting Mexican stereotype who tried to sell corn chips with a side of xenophobia.

Launched in the late 1960s, the Frito Bandito wasn’t just a problematic mascot—he was an all-out caricature, complete with a gold tooth, scruffy mustache, a thick fake accent, and a jingle that sounded like it was pulled from a rejected Looney Tunes short.

He was drawn with all the sensitivity of a middle school textbook doodle, and yet… he made it out of committee and onto American TV screens.

🧀 The Origin Story (Spoiler: It's Cringe)

The Frito Bandito was created by Foote, Cone & Belding, one of the biggest ad agencies in the country, and voiced by none other than Mel Blanc—yes, the same voice actor behind Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck. He debuted in 1967 as the new mascot for Fritos corn chips, owned by the Frito Company (later Frito-Lay).

The premise? He was a cheerful, thieving Mexican bandit who stole corn chips from unsuspecting gringos, sang about it with a smile, and encouraged kids to do the same. His jingle?

🎶 "Ay yi yi yi… I am the Frito Bandito! I like Fritos corn chips, I love them, I do…" 🎶

Yes. Really.

It wasn’t subtle. It wasn’t smart. It was straight-up ethnic stereotyping served with processed cheese dust.

📺 How Was This Ever Allowed?

The 1960s was a golden era of mascots with questionable taste (literally and figuratively), but even then, the Frito Bandito pushed boundaries. He was a direct descendant of the “greaser” stereotype—a trope long used to mock and vilify Mexicans as uneducated, lazy, and criminal.

And yet, he ran for years in national advertising. Frito-Lay ran animated TV commercials, school lunchbox swag, and in-store posters—fully committing to a character whose entire identity was stealing chips and being “lovably” criminal.

It was a case study in how corporate America confused “catchy” with “culturally offensive,” and how racism, when animated and voiced by a beloved actor, could be passed off as “harmless fun.”

😤 The Backlash (And It Wasn’t Immediate)

It took organized resistance to bring the Bandito down.

Mexican-American advocacy groups like the National Mexican-American Anti-Defamation Committee and LULAC (League of United Latin American Citizens) began pushing back hard in the late '60s and early '70s. They ran protests, threatened boycotts, and demanded the removal of a mascot that reduced their culture to a punchline with a pistola.

In response, Frito-Lay tried a half-hearted revision:

They removed the pistols.

They cleaned up his outfit.

They made him look “friendlier.”

But the mustache remained. So did the accent. So did the stereotype.

The backlash grew. And finally, in 1971, Frito-Lay retired the Frito Bandito, replacing him with new characters like W.C. Fritos (based on W.C. Fields) and the Muncha Bunch—because, apparently, old-timey white men and vaguely Western snack gangs were somehow better options.

🔥 Why It Was So Problematic

He portrayed Mexicans as thieving, cartoon criminals

He promoted the idea that cultural mockery = brand identity

He turned a marginalized identity into a snackable punchline

He ran during a time when Latinx Americans were fighting for civil rights—and had to fight a corn chip mascot at the same time

Let’s be clear: The Frito Bandito wasn’t “of his time.” He was offensive even by the standards of his time—and it took real work from real communities to take him off the shelves.

📝 TL;DR

Launched: 1967

Created by: Foote, Cone & Belding (and voiced by Mel Blanc)

Shtick: A gun-toting, chip-stealing Mexican stereotype with a catchy jingle

Retired: 1971 after protests and public pressure

Legacy: A cautionary tale of how brands confuse “cute” with “caricature”

🌮 Final Thought

The Frito Bandito wasn’t just a mascot. He was a microaggression with marketing budget.

He turned a culture into a costume, a dialect into a joke, and a community into a punchline—all for the sake of selling salty snacks. It may have taken years and a lot of protest to bury him, but his legacy lives on as a reminder: If your branding relies on a stereotype, it’s not clever—it’s lazy.

Snack mascots can be fun.

They should never come with a sombrero and a side of systemic racism.

These characters weren’t based on real people—they were based on marketing archetypes, conjured up in rooms with more neckties than self-awareness.

🎥 When Entertainment Furnishes the Fantasy

If advertising built the house, Hollywood helped decorate it—with wallpaper made of nostalgia and denial.

Brands didn’t invent racial stereotypes—they inherited them, lovingly repackaged from the scripts already playing in American theaters and living rooms. Nowhere is that clearer than in Disney’s Song of the South (1946), a film that introduced audiences to Uncle Remus: a warm, smiling Black man who spins magical tales of Br’er Rabbit and other cartoon companions. He’s gentle, wise, endlessly kind… and lives in a world that politely omits slavery, sidesteps racism, and portrays the plantation as a peaceful, pastoral dreamscape.

This carefully curated fantasy scrubbed the brutal realities of the American South until all that remained was a chorus of “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah.” Uncle Remus didn’t just entertain—he embodied the deeply insidious myth of the “happy servant,” a trope designed to comfort white audiences with a version of history that felt charming, nostalgic, and unthreatening.

Hollywood wasn’t just reflecting stereotypes—it was reinforcing and romanticizing them. Song of the South was part of a broader cultural movement that turned the Antebellum South into a storybook setting, not a site of forced labor and racial violence. It framed this era not as a tragedy, but as a kind of quaint origin myth for white American innocence.

Characters like Uncle Remus laid the cultural groundwork for advertising mascots like Uncle Ben, Aunt Jemima, and Rastus. These figures borrowed his tone, posture, and purpose: always smiling, always serving, always safe. They weren’t just marketing tools—they were branding blueprints, carefully constructed to reassure consumers that everything was just fine in the mythic past.

These weren’t harmless throwbacks. They were commercialized distortions—a folksy aesthetic draped over the legacy of slavery and segregation. They didn’t educate; they anesthetized. And they helped sell everything from breakfast syrup to boxed rice to morning porridge.

Because when entertainment wraps stereotypes in song and story, branding doesn’t hesitate to print the label—and slap it on the box.

Disney has since buried Song of the South so deep it makes the Ark of the Covenant look easy to find. But the damage was done. A generation—and then another—grew up absorbing a version of history where Blackness meant servitude, struggle was erased, and cheerful obedience was rewarded with a smile and a sing-along.

📆 The Apology Tour (Now With New Packaging!)

In recent years, brands have attempted course correction. Aunt Jemima became Pearl Milling Company. Uncle Ben became Ben's Original. The Frito Bandito became... unemployable.

These changes, while necessary, often came after years (or decades) of public criticism. The speed of change correlated less with moral urgency and more with shareholder anxiety. But hey, nothing moves corporate mountains like bad PR in Q2.

🧤 A Better Way to Brand

So, what can companies learn from this mess? For starters:

Representation isn’t a costume. If your mascot needs a backstory, make sure it's not lifted from a minstrel show.

Nostalgia isn’t a get-out-of-accountability-free card.

Cultural awareness isn’t optional in a global market—it’s a prerequisite.

People want authenticity. They want to support brands that reflect respect, not relics. And as it turns out, pancakes taste the same without a fictional mammy smiling on the box.

And to those brands that have evolved—thank you. But don’t go quiet now. Recently, social media posts have claimed that figures like Aunt Jemima were real historical individuals “erased” by so-called woke culture. This is false. These characters were fictional—often inspired by racist stereotypes—and promoted by white advertising executives, not based on the lives or legacies of real people.

If your company has made the right move by retiring a harmful brand, take the extra step: educate your audience. Set the record straight. Use your platform not just to rebrand, but to rebuild trust and understanding.

🗳️ How Did You First Learn the Truth About Aunt Jemima or Uncle Ben?

(Multiple choice)

A) School

B) Social media backlash

C) A friend or family member

D) I just learned from this blog post

🟩 Helps track awareness while driving home your educational impact.

🛞 Up Next: Hype, Horsepower, and Humiliation

Overhyped Cars That Turned Out to Be Lemons

What happens when the marketing engine roars louder than the actual car? You get the Edsel, the Aztek, the Yugo—and a legacy of stalled rollouts and burned reputations. Next time, we’re shifting gears from syrup to cylinders, breaking down the vehicles that couldn’t outrun their own branding disasters.

Spoiler: If your car’s only fan is Walter White, you’ve got bigger problems than torque.

Next Blog In This Seven Part Series: 🚗 Overhyped Cars That Turned Out to Be Lemons 🍋 (Part 4)

Final Thought

A brand isn’t a person. But it is a mirror. And what we choose to reflect says everything about who we think our customers are—and who we imagine they want to be.

So next time you see a logo smiling at you, ask yourself: Is it selling a product? Or a past that never should have been romanticized in the first place?

Until next time: stay thoughtful, stay critical, and for the love of breakfast, let’s stop putting minstrel shows on the menu.